Stopping Welfare for Fugitives Accused of Violence: A Rare Law Putting Victim Safety First

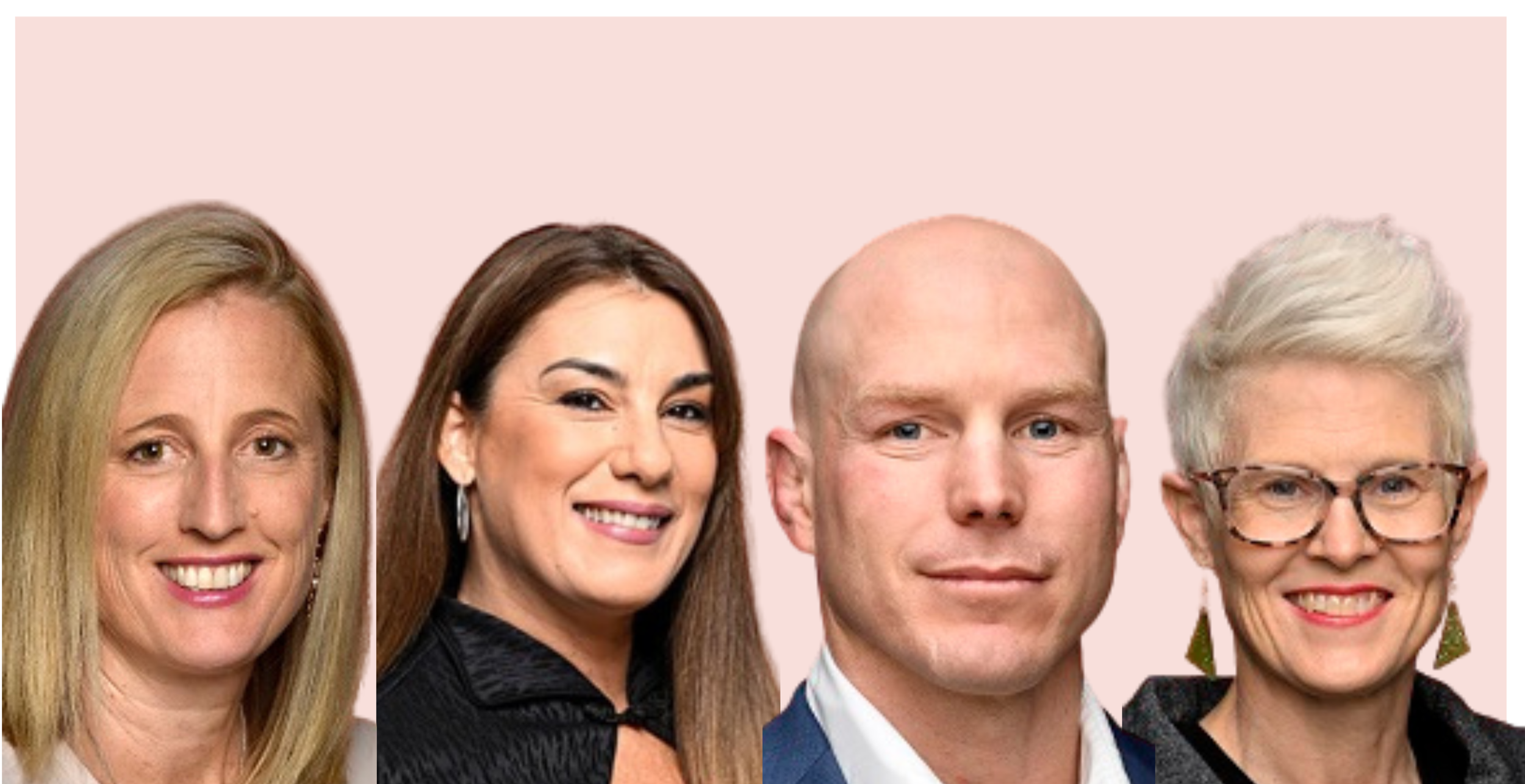

Senators; Katy Gallagher, Lidia Thorpe, David Pocock & Penny Allman-Payne. Photos: aph.gov.au

Australia has quietly introduced a major welfare reform with significant implications for community safety, particularly for women and children. Buried within a technical amendment bill, Parliament has approved a new power allowing welfare payments to be suspended when a person with an arrest warrant for a serious violent or sexual offence is actively evading police.

Supporters call it overdue common sense, stopping taxpayer funds from supporting people accused of the most harmful crimes while they dodge arrest. Critics call it a dangerous erosion of the presumption of innocence. Either way, it represents a sharp shift in how Australia balances rights, responsibility and protection from harm.

The law has a high bar

Welfare payments can only be restricted under this law when a person has an arrest warrant issued for a serious violent or sexual offence such as child abuse, sexual assault or serious domestic violence and police have already met a high evidence threshold for that warrant to exist. It applies only when the individual is actively evading arrest, with the AFP required to demonstrate repeated unsuccessful attempts to locate them and that they are knowingly avoiding police.

This is not a low level compliance tool and it does not affect people who miss an appointment, lodge paperwork late or experience ordinary welfare interactions. It is a narrow high stakes measure designed for a very small group of individuals accused of causing severe harm.

The reality of POI

While Senator Pocock objects on the basis of the presumption of innocence, that concern becomes less compelling in the very specific cases this law targets. These are not disputed allegations, nor early stage complaints; they are matters where police have already gathered substantial evidence and a court authorised warrant has been issued for serious violent or sexual offences.

For a case to reach that threshold, particularly in a system where sexual violence is chronically under reported, under investigated and rarely prosecuted; the likelihood of the allegation being maliciously fabricated is extremely small. In other words, welfare suspension would not be triggered by untested claims. It would apply only to individuals for whom law enforcement has strong grounds to believe they committed high harm offences and who have then made the deliberate choice to evade arrest. Presumption of innocence remains intact but presumption of protection for fugitives no longer does.

What supporters say: closing a dangerous loophole

Senator Katy Gallagher emphasised that this is a narrow and tightly controlled power, explaining that it will be used only in very specific circumstances and rarely applied in practice. She also outlined oversight measures requiring the Commonwealth Ombudsman to be notified each time the power is used, with annual reporting to ensure transparency and scrutiny.

Survivor advocates, meanwhile, highlight the glaring inconsistency that struggling parents can lose payments for late forms, while people wanted for serious sexual harm can continue receiving taxpayer support while in hiding. That contradiction has long been difficult to justify.

What critics fear: due process and unintended harm

Opposition to the measure was passionate and vocal. Senator David Pocock argued that an arrest warrant is not a statement of guilt and warned that punitive action should not occur before a court process. Senator Lidia Thorpe accused the government of harming the most vulnerable, declaring “Shame on Labor… this will demonise people on welfare.”

Crossbench Senator Penny Allman-Payne went further, describing the reform as legislation that so egregiously tramples on people’s human rights. Critics across the chamber fear that an imperfect justice system one that misidentifies victims, disproportionately impacts First Nations and disabled Australians, and risks harming dependents will not support such a power safely. These concerns, they argue, are real and demand robust safeguards.

The law has finally moved toward protection

Survivors and children in this country carry enough, fear, instability, the burden of proof. While they struggle, too many alleged offenders continue life uninterrupted. This reform sends a long overdue message that if you are accused of serious violent or sexual harm, and you choose to run, the public will not fund your hiding place.

Thanks to the ones who introduced and voted for this bill…the rules bent toward survivors. And that matters.

Read the full senate debate here