Two Paths, One Goal: The Women Leading ACT’s Coercive Control Reform

ACT Minister for Women, Dr Marisa Patterson and ACT Liberal Leader, Leanne Castley. Photos: Elise Searson Prakaash

The ACT is moving toward criminalising coercive control — with rare cross-party agreement on the destination but growing disagreement over how fast the Territory should get there.

In interviews with Lady News, Leanne Castley, Leader of the Canberra Liberals, and Dr Marisa Paterson, Minister for Women, both confirmed their commitment to introducing a standalone coercive-control offence — a reform widely recognised as vital to protecting women and children from patterns of psychological and emotional abuse.

But with Labor’s bill scheduled for mid-2026 and Castley re-introducing her private member’s bill in October, survivors and services say the conversation is no longer about if the law will change — but when.

ACT Minister for Women, Dr Marisa Paterson MLA. Photo: Elise Searson Prakaash

Momentum with caution

Dr Paterson said the government’s approach is shaped by lessons from New South Wales, where the first coercive-control prosecutions have struggled to clear high evidentiary thresholds.

“There’s strong community sentiment for this reform,” she said. “But coercive control is complex. We need police, courts, and services trained to recognise patterns of behaviour and build evidence — and we must design laws that don’t unintentionally harm marginalised communities.”

Paterson said the ACT has already begun training for police and courts, launched a multilingual public-awareness campaign adapted from NSW, and set up a steering committee to guide the drafting process.

“We don’t want to build expectations, invite disclosures, and then set the evidentiary bar so high that survivors are turned away,” she said. “That risks retraumatisation and loss of trust.”

The opposition’s push: “Let’s do it now”

Leanne Castley says she shares that caution — but not the pace. Her Crimes (Coercive Control) Amendment Bill 2024 has already been drafted by government lawyers and mirrors NSW legislation with one Queensland clause. She plans to re-introduce it in the Assembly in October.

“Every month we delay means women and children remain unprotected from patterns of abuse the law still doesn’t recognise,” Castley said. “The community expects urgency — and we have the bipartisan goodwill to make that happen.”

The bill proposes to amend the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT) by introducing a new offence — coercive control — applying to a “course of conduct” by a partner or former partner. The conduct must be intended to coerce or control and must be such that a reasonable person would consider it likely to induce fear of violence or seriously impair the person’s capacity to carry out ordinary day-to-day activities.

The maximum penalty would be seven years’ imprisonment. The bill incorporates strict liability for part of the threshold test (the risk or effect of the conduct), allows that the prosecution need not allege each individual incident in detail, and requires the defendant to offer evidence if claiming the conduct was reasonable.

It also includes a review clause to assess the effectiveness of the offence two years after commencement.

In addition, the bill amends the Bail Act (introducing a presumption against bail for coercive-control offences) and the Working with Vulnerable People Act (disqualifying or conditioning registration for those convicted of coercive-control offences).

Castley’s bill includes a 12-month implementation buffer after passage, allowing time for training and awareness before commencement. But she argues the system is ready now.

“We can do hard things,” she said. “If other states can legislate, so can we. Services are ready, the community understands what coercive control is, and police see it every day. They just don’t yet have the legislative tools to act.”

ACT Liberals Leader, Leanne Castley MLA. Photo: Elise Searson Prakaash.

A growing sense of readiness

While the government’s staged approach aims to build solid foundations, many in the sector say the groundwork has already been done. Frontline services have completed extensive workforce training, police have received specialist domestic- and family-violence instruction, and community-education campaigns have run across Canberra for more than a year.

“We’ve raised awareness, trained our staff, and supported survivors through systems that still don’t name what they’ve endured,” one service provider told Lady News. “The groundwork is done — it’s time for the law to catch up.”

Others point to the human cost of delay. With coercive control a known precursor to homicide, advocates argue that continued postponement leaves gaps in protection.

Implementation and inclusion

Both leaders agree that reform must be more than symbolic. Paterson said the ACT has an opportunity to consult deeply with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, multicultural and LGBTQ+ communities, and women with disability — groups that experience higher rates of violence but also face greater barriers in the justice system.

“There’s a great opportunity in the ACT to engage marginalised voices so our law reflects the realities of those most affected,” she said.

Castley, who has spoken publicly about her own family’s experience, says consultation can continue alongside implementation.

“We’ve talked about this for so long,” she said. “We can refine as we go — but we can’t keep waiting.”

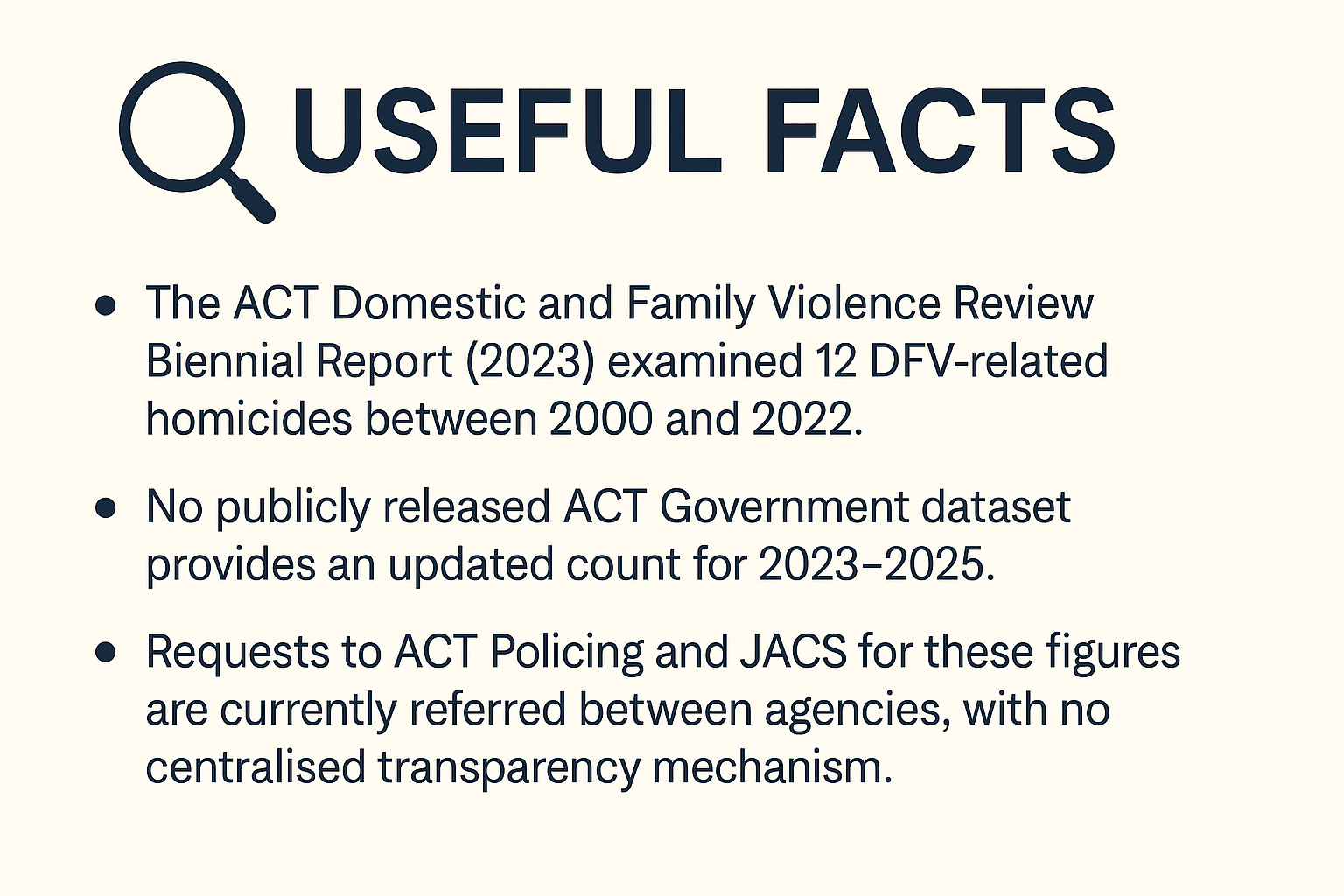

Transparency remains a missing piece in the ACT’s domestic-violence response. While New South Wales and Queensland release annual family-violence death reviews, Canberra’s last public accounting stops at 2022. Advocates argue that without up-to-date homicide data, the community can’t measure whether prevention efforts — or delays in reform — are saving lives.

“Get it right — together”

Paterson said she wants to maintain the Assembly’s record of unanimous support on domestic- and family-violence legislation.

“This shouldn’t be a political point-scoring exercise,” she said. “On an offence this complex, we’re better off getting everyone around the table and getting it right together.”

Castley agrees collaboration is both possible and necessary.

“If the Government wants its name on the bill, fine — I’ll still support it,” she said. “What matters is protecting people sooner.”

Reflecting on how far Australia’s legal culture has come, Paterson said the shift in attitudes gives her hope.

“What’s incredibly depressing, but heartening at the same time, is when you go back and look at judgments from just 20 years ago,” she said. “They’re distressing to read — often cases where a husband became jealous and murdered his wife because he thought she was having an affair.

“And the courts would go down the track of was she having an affair? as if that question mattered. That was only about twenty-two years ago — in our lifetime. And those were the beliefs held by the very institutions that upheld our society.

“But look how far we’ve come. We have come a long way. So there is hope.”

Victim-survivors are watching the clock

For many victim-survivors — particularly mothers navigating family court — the question isn’t whether coercive control will be criminalised, but how soon the law will start protecting them.

Several readers told Lady News they’re exhausted by short-term Family Violence Orders and repeated court appearances. Unlike the ACT, where orders typically last up to two years, South Australian protection orders are ongoing, meaning survivors don’t have to repeatedly return to court to prove ongoing risk. Advocates say this approach reduces retraumatisation and should be considered as part of broader reform.

As the ACT refines its law, many say the impact of criminalising coercive control will extend well beyond the criminal code — shaping how family courts, protection orders, and support services recognise patterns of abuse and risk. By naming coercive control as a crime, the law has the potential to reframe how judges, lawyers, and frontline workers understand the dynamics that trap victims long before violence becomes visible.

“If implemented with care, this reform could finally close the gap between criminal justice and family law — protecting those who’ve already lived abuse, sparing them the retraumatisation of having to prove it again, and making those who use violence think twice.”

For victim-survivors across the ACT, the hope is that this law won’t just define abuse — it will finally protect those who’ve already lived it, and make those using violence think twice.

Which law would arrive sooner?

At first glance, Leanne Castley’s bill appears to fast-track reform — but it includes a 12-month implementation buffer to allow for training after passage. Dr Marisa Paterson’s plan, by contrast, completes that work before introducing the bill in mid-2026.

That means both approaches could, in practice, bring the new law into effect around the same time — mid-to-late 2026.

The difference lies not in the calendar, but in philosophy:

Castley’s model says “legislate first, implement after.”

Paterson’s model says “prepare first, legislate after.”

However, services across the ACT are growing impatient. Many argue that police and agencies have already been trained, and that the sector is ready. As one advocate put it:

“Awareness without action still leaves victims unprotected.”

Whether the bill passes this year or next, one thing is certain — coercive control will become a criminal offence in the ACT by 2026.

As Leanne Castley told Lady News:

“It takes enormous courage to leave an abusive relationship. To every survivor, I’d say: you are remarkable. Keep going, keep protecting your family, but remember to care for yourself first — put on your oxygen mask before helping anyone else. Have faith, stay strong, and know that I’ll keep fighting until coercive control is finally criminalised.”

If you need support

1800 RESPECT (24/7) — 1800 737 732

ACT Domestic Violence Crisis Service — (02) 6280 0900

In an emergency, call 000